This post is presented in collaboration with Active Minds, the national organization dedicated to empowering students to speak openly about mental health.

Please note: This piece talks about a specific experience regarding suicidal thoughts and hospitalizations. Not all experiences will be or are the same.

October 10, 2017 - When someone is actively suicidal, we often tell them to call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, call 911, or go to the local Emergency Room. These are all correct responses, but they are also scary, big steps for someone in a mental health crisis to take. I am going to try to demystify what happens at the emergency room when you go there for suicidal thoughts and planning by sharing my own experiences.

After telling the ER staff the reason why I was there, I was evaluated.

Whenever you go into the ER, for whatever reason, you tell the staff why you are there. You can word this however you want: I am feeling suicidal, I have a suicide plan, I’m having suicidal thoughts, I’m feeling really depressed, etc. I went with my parents, so they talked to the staff for me because I was unable to. (If you feel as though you need support, it’s a good idea to go with your parents or guardians or someone you trust.)

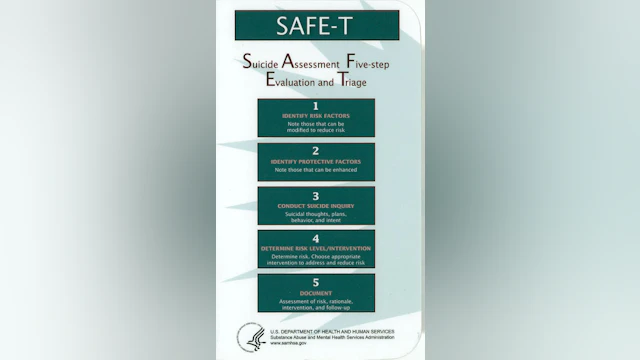

In my visits to the ER, they have had a mental health crisis professional come to evaluate me. The evaluation is assessing your suicide risk to determine what level of care you need. This means that you should be extremely honest with the person- they are just trying to get you the help that you need and that fits your situation. I was asked if I have a plan, if I’ve had previous attempts/thoughts/hospitalizations, what medications I am on (if any), any issues going on in my life, and other questions to determine my mental state.

My level of care needed was determined and they found me a place in that level of care.

In mental health treatment, there are different levels of care, meaning how much supervision and treatment you need.

- Inpatient hospitalization (IP) is 24/7, acute care and support. You spend both days and nights there. Depending on your area, it may be a floor of a regular hospital or a freestanding psychiatric hospital. This treatment is also at behavioral health hospitals or clinics. Inpatient hospitalization is used when the person is at risk for harming themselves or someone else. The average length of stay is 5-7 days, but varies greatly. Since this is usually the outcome for an actively suicidal person, I will explain more about this treatment below.

- Partial hospitalization program (PHP) is an outpatient day treatment where you are there for 6+ hours either everyday or every week day. Outpatient means you sleep at home. This can be at the hospital, at a behavioral health clinic, or at a mental health care center. Partial hospitalization treatment usually consists of 1:1 therapy, psychiatry, group therapy, psycho-educational groups, and recreational/expression therapy.

- Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) is about 3-4 hours, usually at night or in the afternoon, and is 3-4 times a week, Like partial treatment, you sleep at home. This option is used a lot in situations where the person is safe enough to be unsupervised but is struggling enough to need more intensive care than weekly therapy. This can also be done fairly easily in conjunction with school and/or work.

- Outpatient Treatment is your typical weekly therapy/psychiatry/group meetings. Sometimes if a person is safe but is experiencing suicidal thoughts and they don’t do Intensive Outpatient, they will do regular outpatient 2 or 3 times a week with their therapist or do weekly sessions with their therapist and supplement with a weekly group therapy session.

Inpatient hospitalization is there to keep you safe and stabilize you.

Each time I have been to the ER for suicidal thoughts, the evaluator decided inpatient was needed for me. Following this decision, they talked to my parents and I about the different hospitals in the area but explained that they might not all have beds. I was in the ER for several hours while they found a bed, I get blood taken, and they ran some tests. My inpatient program was not at the hospital the ER was in, it was in a freestanding behavioral health hospital, so I was transferred by ambulance. (Though one time they did let my parents take me since we had been waiting for over 6 hours and would have to wait longer for the ambulance.)

I’ll be honest, inpatient hospitalization is not a vacation. You lose a lot of freedoms in inpatient treatment. In my experience, they took away anything that I could possibly hurt myself (or others) with- shoelaces, strings in clothes, belts- anything sharp and anything long. But, I had to understand that it is for my safety. Being inpatient meant that I was a danger to myself and determined not safe unless under 24/7 care- I was monitored closely to make sure I was safe. During my time inpatient, I received 1:1 therapy, psychiatry, checks every 15 minutes or so, safety planning, recreational therapy, skills building, discharge planning, and expressive therapy.

Inpatient hospitalizations are not meant to make you better, they are meant to get you stable and get you out so that you can get the true treatment you need. Care doesn’t end after an inpatient hospitalization and you are not cured because of it- you are simply deemed safe enough to transfer to a lower level, less intense version of care.

Don’t be scared of getting the help you need

While inpatient hospitalization can be scary, it’s also life-saving. I have been in this type of treatment several times after going to the ER and being evaluated. Each time has been different, but each time I learned something valuable. I first experienced the healing powers of art therapy while inpatient. I played piano and basketball while inpatient. I made a good friend while inpatient. I had conversations that helped me see more clearly while inpatient. Leaving everything you know and love and having very scarce contact with the outside world sounds terrifying, but sometimes it’s exactly what we need at that time.

If you get evaluated and are placed in a lower level of care, try to not take that as “you’re not sick enough.” I know that those feelings can come up sometimes in those with mental illness. Inpatient treatment is not a gold star you get that proves you are ill. Your illness is valid, no matter the treatment. The evaluation is just to get you in the correct treatment you need at that moment. Try not to let it get to the point where you need inpatient- reach out and get help before you hit that crisis point.

When in a mental health crisis, it can be so hard to see clearly. Research hospitals around you beforehand and find out what they do for behavioral health cases. Some hospitals near you may be more equipped for mental health crisis situations better than others. Here are some questions you or someone you trust who is with you should ask during these times. If you are someone who lives with suicidal thoughts, knowing what to expect can help ease some of the burden of getting help. Don’t hesitate- you can do this!