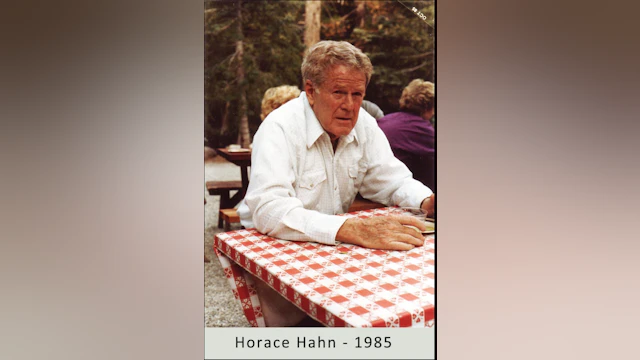

In the fall of 1973, during my second year of law school at the University of Southern California, as was the custom, I interviewed on campus for a summer clerkship with several Los Angeles law firms and was invited back for more extensive interviews to a few of them, including the mid-sized corporate firm of Hahn Fraser. After a full afternoon of interviews, my last one was with the senior name partner, Horace L. Hahn. Mr. Hahn was at the time 55 years old – hard to believe I’m now fourteen years older than him as I write this. I was a baby-faced 23-year-old and had been married a whopping three months.

I was seated opposite him at his leather topped desk occupied by a couple of neat stacks of papers and an ashtray full of butts of unfiltered Chesterfields – my mother’s brand. The walls of his corner office were paneled in dark oak and the windows covered with shutters made of the same wood. Mr. Hahn was ruggedly handsome with close-cropped reddish-gray curly hair, broad shoulders, military-like posture, and a deep booming voice and boisterous laugh. Although I rarely pay attention to these kinds of things, I couldn't help but notice the gold ring on his right hand – two eagles with their wings outstretched, perched on opposites sides of a diamond. He spoke with an air of aristocracy. I instantly liked him.

We chatted for a few minutes about this and that – I don't remember what – and then he became very serious. He leaned forward with both forearms on his desk and, with his wolf-like gray eyes boring into mine, asked – no, demanded to know – "Mr. Gauntt, what is the worst thing that has happened to you in your life?" I was momentarily stunned by the question.

No one in my other interviews asked me that. In fact, no one had ever asked me that. There was no doubt about my answer; only a brief hesitation of whether to take the easy way out—‘Uh, I didn’t get into Stanford law school’—or open the door to my dark basement I rarely entered.

"My father died by suicide a few days before Christmas in 1970. He took his life at his office the night I came home to Itasca, a Chicago suburb, for the holidays. We thought he was in Panama on a business trip and returning home the next day. My mother woke me the next morning with the news and I came out to the living room with my thirteen-year old sister to meet with two DuPage County Detectives. I was twenty years old and a junior at USC."

I can't specifically recall what either of us did next. He may have said something like, "Thank you for telling me that," and I might have said, "I never talk about this and I'm not sure why I told you." But what I do know is that at that moment, a bond was formed between us that would only become stronger over the next 30 years right up to his death in 2003. Horace Hahn became like a second father to me. He had no children of his own. I wear his eagle ring every day. Oh, and I got the job.

Shortly after starting at Hahn Fraser as a full-time associate in September of 1975, I began to work with Brian, a senior associate specializing in everything that wasn't litigation. Brian was a very bright, hard-working, energetic and excitable lawyer. He was impulsive and prone to fits of temper. I worked closely with him and he trained and mentored me in a wide variety of interesting real estate and corporate matters.

Brian was intemperate. He liked to get a drink or two after work and he asked – dragged – me along many a time, much to my wife, Hilary’s, chagrin. There really was no such thing as "one or two" with Brian. More like five or more, and always scotch and sodas, tall. However, this time spent with Brian was invaluable. This is where I learned everything about firm politics, how the partnership worked, the compensation system, what you had to do to make partner, how the personalities of the partners shook out, who to work for and who to watch out for. I also got all the gossip and details of what went on in the partners meetings. Brian made partner about a year after I started.

Brian was also very ambitious. He had landed a new client, Steve Bronco, about his age, also a lawyer, who was starting a new bank. Brian often railed against the injustice of his clients making so much money, far more than he was as a lawyer, when he was infinitely smarter and they were piggybacking on his intellect to make their fortunes. Brian also did not hide from his partners, or me, his feelings that he was undercompensated and underappreciated by the firm. So, in 1978 Brian left Hahn Fraser and set up his own firm. He continued to do a lot of work for Steve and his new bank and, shortly thereafter, quit his law practice and went to work full time for the bank and reap his fortune. Hilary and I moved to Solana Beach, CA in 1979 and I went to work for Hahn Fraser's recently opened San Diego office. Brian and I lost touch.

Three years later, a Wednesday afternoon, Brian called me from out of the blue and asked if I’d heard the news. “Yes.” I’d recently read in the papers that a criminal indictment had been filed by the U.S. Attorney in Federal Court in San Diego against Steve, Brian and others involving bank fraud. Brian said he was in San Diego and asked if I had time to get a drink. “I’d really like to talk to you, but understand it’s short notice and all.” There was something in his voice.

"Sure, where do you want to meet?"

"Well, actually I'm calling you from the bar in your building. I've been here a while."

When I got there a few minutes later, he was sitting at the bar and on the phone. We shook hands and he gave me the "one minute" sign. I found an empty booth in a corner and slid in. When he got off the phone he came over with his drink (scotch rocks) and, Horace Hahn-like, boomed, "Casey Gauntt! How the hell have you been?" Brian ordered a back-up from the trailing waitress and for me – the usual – Dewars soda, tall.

He asked about Hilary and our daughter, Brittany, who was two. Brian said he and his wife, Maryann, and their two teenage daughters were still living in their fabulous house in Glendale, a classic, designed by Green and Green. We talked about Hahn Fraser and some of his former partners. I'd made partner two years earlier. Brian was smoking, Winstons as I recall, and I bummed from him the first of several that night. "Gauntt, don't you ever buy your own cigarettes?" Sometimes. In those days I liked to smoke when I was out for cocktails.

After a half hour of catching up, and a fresh round of drinks, the conversation turned serious and Brian laid out the misdeeds of the bank to hide liquidity problems. “At first I didn't realize what was going on. Then I did, and I became involved. I should have quit right then. I thought we could work the bank out of its financial problems before the regulators figured out what was really going on. It was stupid, wishful thinking.”

The bank was seized by the regulators, he was out of a job, and the criminal charges had been filed against them. Brian was broke. He'd already spent a small fortune, his savings, on his criminal defense attorneys and was afraid he was going to lose his house; everything.

Brian continued, "Ok, here it is. This afternoon my lawyers and I met with the U.S. Attorneys handling the case and we cut a deal. I will plead guilty to some felony charges and cooperate with their investigation against the others and, in return, their office will recommend a sentence of 5 to 8 years. It will be up to the judge – could be more, could be less – bottom line, I'm going to jail." His head and his shoulders slumped; he looked beat and defeated.

“When does this happen?” I asked. He said it would take a couple of days for the plea agreement to be prepared and then several weeks before he went before the judge for sentencing.

"I'll lose my ticket, you know. When you plead to felonies like this the California Bar takes your license. I'll never be able to practice law again. Hell, I'll never get another job."

Brian stared into his near-empty drink for a long time and then looked sideways. With the back of the hand not holding the cigarette, he rubbed away the tears that began to fall from his puffy eyes – his shoulders shaking. "Casey, I screwed everything up. I've thrown it all away. Everything. My girls – how can I tell 'em? How do I go home and look at my wife and my girls and tell them ‘Guess what? Daddy's going to jail.’ Oh, for God's sake, how the hell can I go to jail? How do I do that?"

And then he got very quiet before he looked at me and said, "I can't."

It was the way he said it – the look – the hollow sound in his voice. He had made a decision; one he'd probably been turning over in his mind for weeks. I saw the cocktail waitress coming with another round. I waived her off and she spun away on her heel. We spent the next hour locked in the most serious conversation I’d ever had with somebody.

“Brian, I know this is bad. It's hard to imagine how you will ever be able to live with this or get beyond it. I know you think this will never get better; it will only get worse. But I need to tell you something and I'm speaking from experience. You know my father killed himself in 1970. Right?" He nodded.

"I was twenty. My sister was thirteen, in the eighth grade. Laura adored my dad. He was her favorite person in the whole world – her knight in shining armor– and she was his princess. Brian, I know you think if you check-out that will make it better for your family; make it easier for them. Take it from me, it won't. It makes it worse. And it's worse for a long, long time. Maryann and your girls will be hurt and embarrassed if you go to jail, and they will cringe when asked by their friends ‘Where’s Brian?’ ‘Where's your dad?’ ‘What does he do?’ Most of them already know. Bad news spreads fast. And your girls will eventually deal with it. But Brian, they may never be able to deal with the loss, the emptiness, if you check out. I haven't, and it’s been twelve years since my dad took his life. My sister hasn’t. My brother hasn’t. If you do this, you won’t go to prison. But, believe me, you'll be handing your wife and daughters a life sentence."

I told Brian about my dad's and his company's financial problems.

"Your problems are bigger than what my dad was facing. No question. But bottom line, I don't care how bad it gets for you. It will never come close to the pain and trauma you will bring onto your family if you do this. Brian, your family loves you; they want you; the rest of this crap will fade away. You have to ride this out for your girls."

We both were crying at this point.

We talked a little more and I encouraged – begged – Brian to check into the hotel next door. I walked him up to the check-in desk to make sure he did it and asked him to call me in the morning. I drove home, a stupid thing to do given "the couple" of drinks I had, but the adrenaline was pumping and all my senses were firing. I hoped I’d get that call, but I wasn't sure. I got to the house around midnight; my wife and baby were sound asleep.

In the morning I awoke, exhausted and hung over, and was back at the office around eight. I debated whether to call or go down to the hotel and see if Brian was still there. I admit a big part of me was afraid to find out, so I ended up doing nothing, except worry.

A couple of hours later I got a call. It was Brian and he was back in Glendale. He said he got up early and drove home. He had just finished telling Maryann about the plea bargain, and they would tell the girls when they got home from school. He sounded pretty good. He said he'd probably be back in San Diego in a few weeks and maybe we'd get together then. He signed off with, “And thank you...for everything.”

Brian ended up serving a little less than two years. I saw him a couple of times after he got out, the last at a retirement party for Horace Hahn in March of 1987. Shortly after his release, Brian went to work for one of Horace’s long-time clients. He had stopped drinking and looked as fit as I'd ever seen him. Brian and Maryann were together and his girls were doing well. He seemed happy. That was the last time I saw or spoke with Brian. He died of pancreatic cancer in 2002.

……………………………………………………………………………

At around 12:30 pm on Friday, August 15, 2008, Hilary and I exited the Mandeville Auditorium on the UCSD Campus in La Jolla, California. The memorial service for our 24 year-old son, Jimmy, had just concluded. We watched his friends, his pallbearers, lift his casket into the hearse parked next to the auditorium. We did our best to greet and hug as many as we could of the over one thousand family and friends in attendance. Six day earlier, Jimmy was walking home from a party in the early morning hours and was accidentally struck and killed by an automobile.

A woman came up to me. She appeared to be in her mid-sixties. I didn't remember her name, but she looked familiar. I went to shake her hand, but she gave me a hug instead. "You may not remember me. I'm Maryann. Casey, I'm here for you today because you were there for Brian and us all those years ago. Thank you and God bless you and your family."

She walked away wiping tears from her eyes, as I did from mine.