One month before I flew cross country to enter residential treatment for an eating disorder in May 2013, my friend and college varsity tennis teammate Paige died by suicide. On the day I entered treatment, another woman from New Jersey had also been admitted. When I told her my hometown and the N.J. college I was attending, she said, “Oh isn’t that where that girl just died?” I told her it was and that she had been my friend. An awkward silence followed.

I hadn’t processed Paige’s death yet. My eating disorder had developed two years prior as a coping mechanism for my undiagnosed anxiety, depression, and OCD; homesickness after the transition to college; my stress at the collegiate workload and the expectations I felt being on the varsity tennis team; childhood micro-traumas; and more. Following the news of my friend’s death, I leaned further into my eating disorder, using unhealthy behaviors to numb myself rather than feeling and processing this new trauma. I attended her funeral, but didn’t make it to her burial (which was walking distance from my parents’ house) because it had been four hours since I’d last eaten – and one of the many “rules” dictated by my eating disorder required that I eat precisely every 3-4 hours. I still regret this.

In hindsight, I realize there were warning signs that preceded her suicide. But none of us knew them at the time. I, at least, thought suicide only happened in movies and to “crazy people” – a harmful stereotype. Paige started mentally declining a month before her death. She had stopped sleeping; began hyper-focusing on a problem she was experiencing in one class, and then stopped caring about all of her classes (notable for an honors student who had just been accepted into nine law schools); her eyes appeared glazed over as if she wasn’t really there with you; her speech slowed and seemed to take great effort, as if it was hard for her to pull words out of her brain to form sentences; her weight drastically changed; she distanced herself from her partner, friends, and family; and more. She had one month left of college, so we were all just trying to get her to graduation. Then, we figured, she’d be able to take time off before law school to prioritize her mental health. She didn’t make it to graduation.

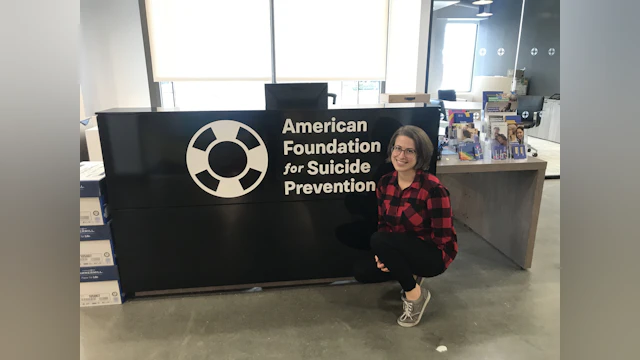

This suicide loss, and my eating disorder recovery journey, fundamentally changed my values and who I was as a person. In 2016, I secured my first full-time marketing job, at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

By working at AFSP, I felt I was able to honor Paige and apologize for not realizing how bad things in her brain had been, though I know that her death was not my fault. In the four years I worked for AFSP, I learned so much about suicide and mental health. I also became comfortable speaking publicly about my eating disorder for the first time.

Five months after leaving AFSP to follow my dream of moving to Portland, Oregon – just two hours from where I went to residential treatment years earlier – the world shut down because of the pandemic. It was during this time that one of my few close Portland friends started acting strangely. I’ll call them Sam. I hadn’t seen Sam in person for several months because of social distancing guidelines, but a family member of theirs from out of state reached out to a group of Sam’s friends for help because Sam hadn’t been doing well, and had stopped answering their phone.

After my experience losing Paige and then working in suicide prevention, I took any mental health scare seriously. I volunteered to go to Sam’s apartment to check in on them. It was after the first snow of the season and I learned the hard way that my car battery had died. I called another mutual friend to pick me up and we drove over to Sam’s together.

When we got there, the door was ajar and Sam was not acting like themself. I immediately recognized many of the same warning signs Paige had displayed, and I was determined not to lose another friend. It was extremely triggering and scary. But after years of working in suicide prevention, I knew what to do. We convinced Sam to get into the car and we brought them to the ER. Sam stayed in the hospital for two weeks, getting help.

I was numb. This experience brought up a lot of memories of Paige. I leaned on my therapist and mom, and I did not relapse on my eating disorder.

It’s been close to two years since Sam’s mental health crisis and they are 100% back to themself again. The crisis has long passed. Sam is okay.

I still think of Paige often. This spring marked ten years since her death. We only knew each other for three years, and I had spent most of them preoccupied with my eating disorder. I wish I could’ve had the opportunity to be her friend once I had healed. But I don’t know if I’d be the person I am today if I hadn’t lost her. I certainly wouldn’t have worked for AFSP, and I don’t know if Sam would still be here. Life can be strange and complicated and heartbreaking in that way.

I miss Paige – and I do my best to honor her memory by teaching others the warning signs for suicide, what to do in moments of crisis, and how to have a #RealConvo about mental health and suicide.