Jul. 27, 2018 - Suicide loss survivors are taught that we never get over our loss; we just learn to live with it. After losing my 19-year-old son Paul to suicide in September 2006, I found – eventually – that life will be different, but it does go on – and can still bring us experiences we will always cherish.

One way of coping with grief is to re-immerse yourself in an activity you enjoy. Before losing Paul, I had raced short triathlons, which involve swimming, cycling, and running. Because Paul had died in a swimming pool, however, the thought of swimming seemed fraught with psychological complication.

In February 2008 I made the decision to challenge myself by entering the lottery for Ironman Hawaii. While only the 1,500 best triathletes in the world qualify for the race, 200 lottery winners are allowed to join them. I paid the $70 lottery fee, knowing I was probably wasting money on a 50-1 chance to start a race I didn’t think I could finish. I am a terrible swimmer, so the prospect of swimming 2.4-miles in the Pacific Ocean within the allowed time limit was daunting. Even if I made that time cutoff, I would have to bike 112 miles and run 26.2 miles through the heat, humidity and wind on the Big Island.

That April, I saw my name on the list of lottery winners and immediately thought to myself, “What have I done?” I knew I would need to begin swim training again. Plus, I realized that by race day, everyone I knew would be aware I was doing this race; there was a good chance I would suffer the public humiliation of being one of the nearly 100 racers who annually drop out or miss the time cutoff for one of the events.

My only hope was to take to heart the Ironman motto, “Anything is possible.” Completing the race may seem impossible, the motto indicated, but with proper training, any healthy person could finish.

I accepted my spot, forced myself to get back into the water, and after six months of intensive swimming, biking and running, my family and I flew to Hawaii.

The night before the race, my fear of failure made me feel like a soldier on the eve of a big battle. It was also a time to reflect on how the next day would be bittersweet. As parents, we raise our children hoping they will let us share some of their lives just as we hope they will want to share some of ours. Somehow, that had been taken away from my family. Tomorrow, I thought to myself, Paul should be standing right next to my wife and daughter, cheering on his father. It seemed wrong to do this in his absence.

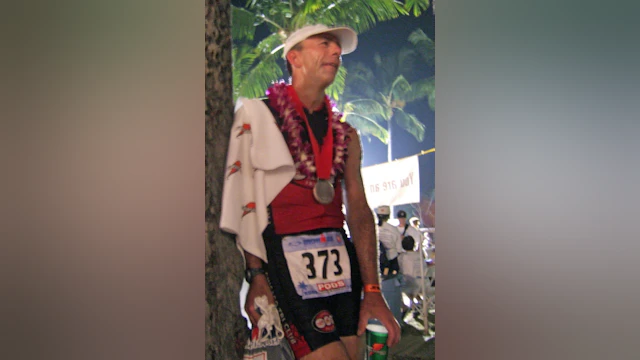

The next morning, after a frantic sprint to the finish, I beat the swim cutoff by the thinnest margin in Kona history: five seconds. After having narrowly escaped disqualification, my lengthy training paid off and I successfully biked and ran through the steamy Hawaiian weather. NBC ended their coverage of the event by showing me, the guy who barely survived the swim, crossing the finish line.

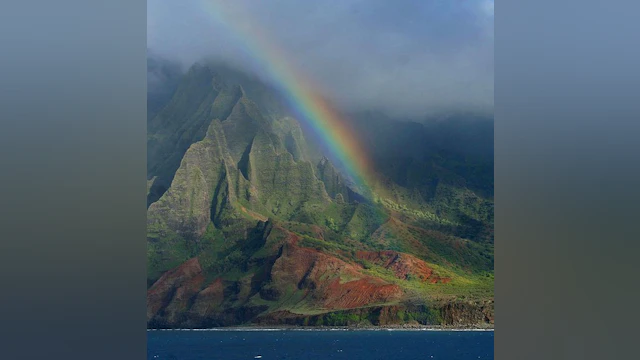

A few nights after the race, my wife and I went to a spot on the other side of the island where lava flows down a mountain into the sea and explodes as it enters the ocean. There was a full moon that evening, which is something we always associate with Paul. One of his friends had written a choral piece for his college’s memorial service that featured following lyrics:

You are the full moon,

burning bright over the pond garden,

our friend,

and we know where to look for you in the sky.

A brief shower passed and a rainbow appeared directly over the lava. I was stunned. How was that even possible? I later learned that a lunar rainbow requires perfect conditions: a bright moon, minimal light pollution and precise angles. Few of us will see one in our lifetime, and most likely it will be colorless. Yet I saw a bright, colorful lunar rainbow exactly when I needed it. Maybe the universe had favored me with a moment of synchronicity or maybe it was just a lucky coincidence. Nevertheless, a small part of me likes to think it was Paul saying, “Nice going, Dad.”

In retrospect, the entire experience – deciding to risk failure, facing up to my fear of water, the months of training, the race, the rainbow – changed my life. After I returned home I felt the desire, and knew I had the ability, to make a difference in the world. Three months after the race, I joined the board of directors of the Illinois chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. When AFSP later adopted the mission statement “to save lives and bring hope to those affected by suicide,” I knew I had made the right decision.

During the years that have passed since my Ironman Hawaii race, I’ve come to realize that the Ironman motto “Anything is possible” isn’t about physical training. It is a tribute to the human spirit. Sacrifice, discipline and perseverance can allow us to achieve what may seem impossible. Applying that concept to my life as both a suicide loss survivor and now as a suicide prevention advocate, I understand that Paul’s death did not preclude me from having a fulfilling life. I truly believe that the slogan, “A World Without Suicide” isn’t an impossible goal; it is our future.

Click here to learn how to become a suicide prevention advocate with AFSP.